The New England Food System Planners Partnership has just released Connecticut’s Local Food Count 2022 and a New England-wide Regional Food Count 2022, shedding light on local food spending across New England. The Local Food Count 2022 reveals that $709 million or 2.7% of the state’s total $26.3 billion in food, beverage and alcohol expenditures were spent on local and regional products. This report is crucial in the journey towards a more resilient and self-sufficient food system.

Want to know more? Click here to dive into the details and see how you can support the goal of 30% local food consumption by 2030.

In this report, ‘local’ is defined as food grown or produced in Connecticut and ‘regional’ is defined as food grown or produced in New England. The report estimates spending on local products at grocery stores at $239 million (4.2% of total grocery store spending), spending via direct sales channels—farmers markets, CSAs, farm stands—was considered 100% local, as were home production (e.g., gardens) and donations. Spending on local products at full-service restaurants was estimated at $120 million (3.0% of total full-service restaurant spending), while schools and colleges accounted for $51 million (6.9%). “Food furnished and donated,” which includes food served at hospitals, prisons, and assisted living facilities, accounted for $30 million (3.9%). Accompanying the local food count is an interactive data dashboard, enabling a look at the Regional and State level results.

“Most of us get most of our food from the grocery store, so grocery retailers are key players in reaching the 30% goal. New England farmers and fishermen need more access to the market channels that are part of our daily lives,” said Meg Hourigan, Coordinator of the Connecticut Food System Alliance, member of the New England Food System Planners Partnership.

Residents and Business Owners Encouraged to Choose Local Food!

For New England grocery stores, restaurant owners and chefs, sourcing local and regional food can be an economic boost for businesses in the region. By including better signage and labeling on shelves or featuring menu items that promote local farms, seafood, and other seafood producers, this commitment from New Englanders to New Englanders drives sales, keeps dollars close at home and supports jobs for the community.

Institutions such as colleges, hospitals, and schools, have already implemented strategies to expand local and regional food offerings; more can be done through state policy and funding commitments.

“In New England, we have incredible farmers, fishers and producers as well as food businesses, restaurants and institutions that care about growing, sourcing and providing local and regional food to our communities,” said Leah Rovner, Director of the New England Food System Planners Partnership. “New Englanders and visitors alike want to support these businesses and need to be given increasingly more opportunities to do so.”

Residents and business owners can help strengthen our regional food economy by choosing local and regional food when making purchases, keeping our dollars closer to home.

“The single best way we can make a difference now is to choose local and regional food items over those from far away. By shifting even just $10 per week from your existing current food purchases to local or regional food items goes a long way toward supporting our regional food economy,” said Rovner.

The Need to Capture Future Local Food Counts

This data serves as a baseline for future assessments, with subsequent counts planned for 2025 and 2030. The report also identifies gaps in current data, such as specific product details, and suggests areas for improvement in both data collection and local food system support.

Goal: 30% Consumption of Regional Food Products by 2030

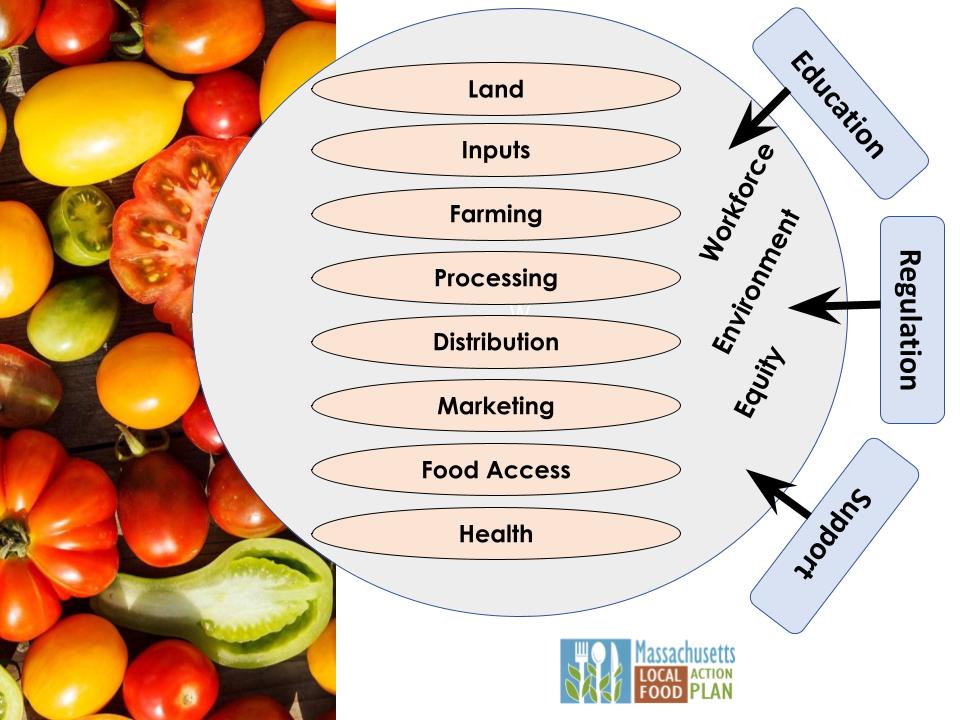

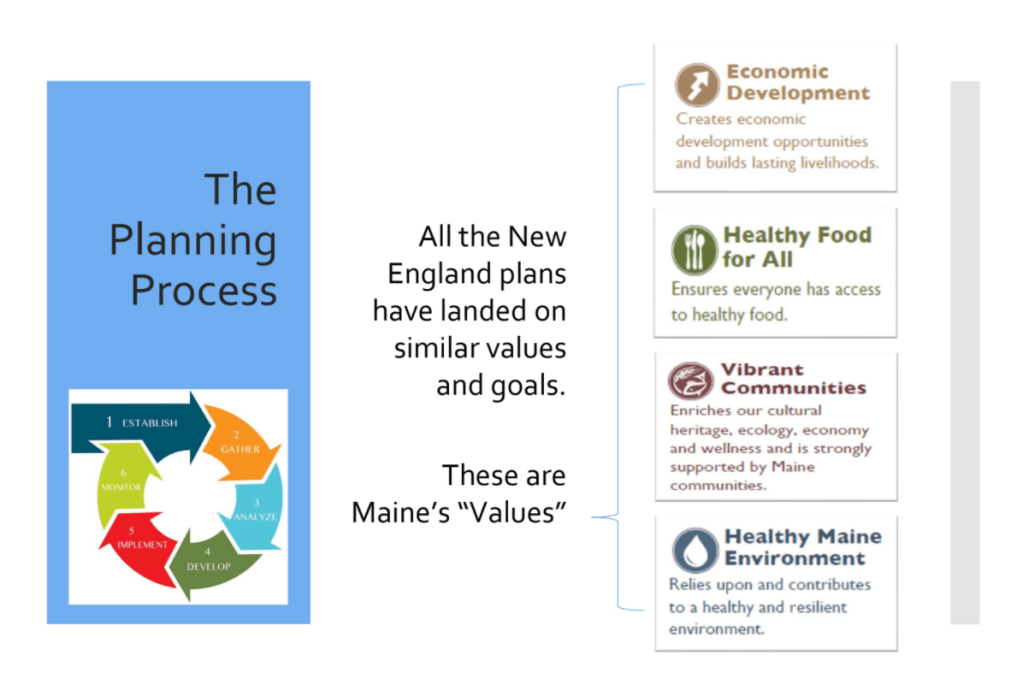

The local food count data collection is part of a greater effort to reach a regional goal of producing and consuming 30% of New England’s food needs in the region by 2030. In 2023, the New England Food System Planners Partnership, a collaboration between seven state-level organizations, six-state agricultural, economic and environmental department representatives and Food Solutions New England (FSNE), released A Regional Approach to Food System Resilience. The research explores the opportunities and needs along the food supply chain in New England, and highlights the land, sea, and labor needs of the region, consumer purchase metrics, distribution trends, and population projections that will impact the region’s ability to feed itself in the coming years.

The 2022 local food counts project was funded in part by the Connecticut Department of Agriculture through the Community Investment Act (C.G.S. Sec. 22-26j) and managed by the Connecticut Food System Alliance with research provided through the University of Connecticut’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy.

About the New England Food System Planners Partnership

The New England Food System Planners Partnership (NEFSPP) is a collaboration among seven state-level food system organizations, six-state agricultural, economic and environmental department representatives and Food Solutions New England (FSNE), a regional network that unites the food system community. Together, they are mobilizing regional networks to impact local and regional food supply chains and strengthen and grow the New England regional food system. The Partnership disseminates information on trends, challenges and opportunities to hundreds of groups across the region that connect with our individual state initiatives. The Partnership is fiscally sponsored by the Vermont Sustainable Jobs Fund.

About Connecticut Department of Agriculture

The mission of the Connecticut Department of Agriculture is to foster a healthy economic, environmental and social climate for agriculture by developing, promoting, and regulating agricultural businesses; protecting agricultural and aquacultural resources; enforcing laws pertaining to domestic animals; and promoting an understanding among the state’s citizens of the diversity of Connecticut agriculture, its cultural heritage and its contribution to the state’s economy.

About University of Connecticut’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy

The Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy located at the University of Connecticut (UConn) provides economic analysis for problems related to food, the environment, energy, and sustainable economic development.

The Center was named through a gift from alumnus Charles J. Zwick to UConn’s Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics and has since expanded its mission and services. Zwick Center studies seek to provide practical, impartial analysis that supports the functioning of markets and informs decision-makers in the public and private sector. Learn more are.uconn.edu/zwick-center/

About the Connecticut Food System Alliance (CFSA)

Connecticut Food System Alliance (CFSA) is a state-wide network of dedicated stakeholders committed to creating broad systems change and advancing a sustainable and just food system in Connecticut. CFSA builds connections between groups and people committed to our shared goals of food security, food justice, and climate resilience. CFSA is working with partners to develop a state food action plan for achieving these goals. Formed in 2012, CFSA has been fiscally sponsored by Hartford Food System since 2014.